This page aims in the first place at everybody new to this subject. Canon law is another word for ecclesiastical law. The Greek word kanon [κανὠν] means a guideline or rule. Canon law has a history of nearly two millennia. On this page the subject is the law of the Catholic Church, mainly during the Middle Ages. In this period canon law reached great heights and gained considerable importance. Special pages concern text editions for medieval canon law and medieval legal procedure.

Antiquity and Early Middle Ages

The ecclesiastical law of Antiquity was formed on one side during church councils, and on the other hand in cooperation with the secular authorities, or even completely by these authorities. The Roman emperor Constantine acknowledged the Christian belief in 312 with the famous Edict of Milan on religious tolerance. In 325 he even presided over the Council of Nicea. During the fourth century Christianity won more followers. In 380 it became the Roman state religion. In this way Roman law could apply to the Church, too. Therefore the Digest and the Justinian Code from the sixth century are also important for canon law.

Councils and synods are often held under royal patronage during the Early Middle Ages. It is doubtful whether the councils had any great influence at all. There are no contemporary collections of the earliest conciliar decrees. Many decisions were repeated in the acts of later councils. The Carolingians did some efforts towards unification of church life, including canon law. Archbishop Hincmar of Rheims did order the fabrication of falsified canonical collections, which had a great influence on later developments. The most famous falsified collection is the Pseudo-Isidoriana, for which the authorship of abbot Paschasius Radbertus at Corbie was claimed, but currently archbishop Ebbo of Reims comes more into view. Scores of collections came into circulation, varying greatly in volume, range and quality. Church law became locally widely different and difficult to understand. Roman law did not function any more as the example to imitate. There were no law schools. Canon law did not develop along straight paths and (papal) master plans. Another source for canon law are the penitentials, the libri paenitentiales. The ordines iudiciarii inform us about the variety of early canonical legal procedure. The early developments are centuries later still visible. Medieval canon law did not develop along straight lines, nor did the Church.

The classical period of canon law (circa 1100-circa 1300)

About 1050 more systematically organized legal collections arise which outdo older collections in the number of decrees collected. Using a small number of them, for instance the Decretum by Ivo of Chartres, the famous “Concordantia discordantium canonum”, usually called “Decretum Gratiani“, could be created relatively quickly between 1120 and 1140. The texts of the decrees are connected to each other with short remarks (“dicta”). In Bologna one started to teach canon law. Under the influence of the revived Roman law it got a new form and its authority grows. Bishops did ask the pope increasingly for verdicts on their cases. The cases themselves stem mostly from France and England. The pope sent other bishops or abbots as judges delegate to pronounce their verdict. Papal decisions had the form of decretals, letters containing such verdicts. Their number grew particularly fast under pope Alexander III. These decretals, too, were avidly sought after and put together into private collections, which in their turn caused the creation of five great compilationes. The greatest of medieval councils was held under pope Innocent III, the Fourth Lateran Council of 1215. In 1234 pope Gregory IX ordered the Spanish Dominican Raymund of Peñafort to harmonise these compilations and to edit their content into an official collection in five books, often called the Liber Extra, available online with only the text or as a searchable database. Boniface VIII ordered three canonists to compile the next papal decretal collection, the Liber Sextus, published in 1298. Shortly afterwards followed the Clementinae (named after Clement VII) and the Extravagantes Johannis XXII. The allegations of these law books are sometimes difficult to understand, because they were heavily abbreviated.

Like the lawyers who studied Roman law the canonists started to work. Those who studied and commented on the Decretum Gratiani were called decretists. Of them the best known are Stephan of Tournai, Rufinus, Laurentius Hispanus, Geoffrey of Trani and Huguccio of Pisa. Their colleagues who focused on the decretals got dubbed decretalists. Here the names of Bernard of Parma, Johannes Teutonicus, Innocent IV and Henricus de Segusio (Hostiensis, because he became cardinal of Ostia) deserve mentioning. Both decretists and decretalists wrote summae, great syntheses, and lecturae, line by line commentaries. For each collection a standard gloss (commentary in the margins) came into existence. This was done also for the acts of the Fourth Lateran Council.

The interaction between Roman and canon law renewed in particular legal procedure. A kind of “romano-canonical” process was created. Of this the best known canonical feature is the inquisitio, originally a kind of process in which a court starts the investigation (instead of the parties involved). The inquisitio became notorious by its abuse at trials of heretics, and from the 16th century on during witch trials. In his Speculum iuris [“Mirror of Law”] Guillelmus Durandus (circa 1235-1296) created an encyclopedia of legal procedure. The papal courts played a great role in canon law, especially the Rota Romana. Canon law influenced in particular the procedures for elections. It was on matrimonial law that medieval canon law put the most lasting marks.

Canon law from 1300 to 1500

The lay lawyer Johannes Andreae (died 1348) was the most influential canonist of the fourteenth century. He wrote commentaries on many works. The romanist Baldus de Ubaldis (1327-1400), too, wrote a canon law commentary, on the first three books of the Liber Extra. One has called Nicolaus de Tudeschis (1386-1445) the last classical canonist. He was a professor at Siena, abbot of a Sicilian monastery and archbishop of Palermo (hence his nickname Panormitanus).

Canonists worked at the high courts, in the services of bishops and cathedral chapters, they teached at law faculties or made themselves a career in the Church. Some popes were canonists, notably Innocent IV. Francesco Zabarella became the archbishop of Florence and a cardinal (hence also known as Cardinalis). Guido de Baysio was the archdeacon of Bologna (Archidiaconus), and thus also head of the university. Well-known theologians like Jean Gerson, Pierre d’Ailly and Nicolaus of Kues knew their way in canon law. Legal advice in the form of consilia has survived also for canonists, for example from Oldradus de Ponte (see for instance his nrs. 35 and 92), Panormitanus and Zabarella.

Canon law did not just concern the Church. It pertained to both private and public life. Lawyers argued that canon law could apply because of a person’s rank and standing (“ratione personae”), because of the matter involved (“ratione materiae”) and when justice had not been done or sins had remained unremitted (“ratione peccati”). Thus canon law could be relevant for people engaged and married, students, travelers, crusaders, widows, merchants and money lenders.

The study of medieval canon law

Already in the sixteenth century some scholars were interested in medieval canon law. The Spanish bishop Antonio Agustìn did pioneering work in this field during the sixteenth century. A number of old collections is named after their discoverers in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries (Luc d’Achery and the Dacheriana). Baluze, Mansi and Muratori, too, deserve to be mentioned here. In the nineteenth century German scholars like Theiner, Hinschius, Schulte and Maassen took the lead. The twentieth century brings international cooperation, and great scholars like Fournier, Le Bras, Gaudemet, Fransen, Cheney, Duggan, Holtzmann, Heyer, Weigand and Stephan Kuttner (1906-1997) with his Institute of Medieval Canon Law, founded in 1955, since 1996 in Munich. Its library returned to New Haven, CT in 2013.

Literature

First some introductions to medieval canon law:

- Gérard Giordanengo, ‘Droit canonique’, in: Jacques Berlioz et alii (ed.), Identifier sources et citations (Turnhout 1994; L’atelier du médiéviste, 1) 145-176.

- Joseph Avril, ‘Les décisions des conciles et synodes’, in: Berlioz c.s., Identifier sources et citations, 177-189.

- James Brundage, Medieval canon law. An introduction (London-New York 1995; 2nd ed. 2022, edited by Melodie Eichbauer, 2022) – shows canon law and its role in medieval society, with biographies of some canonists and an appendix on medieval references and citations.

- Eltjo Schrage and Harry Dondorp, Utrumque Ius. Einführung in den Quellen und das Studium des gelehrten mittelalterlichen Rechts (Berlin 1992) – first edition in Dutch (Amsterdam 1987); condensed and updated as ‘The sources of medieval learned law’, in: The creation of the ius commune. From casus to regula, John W. Cairns and Paul J. Du Plessis (eds.) (Edinburgh 2010) 7-56.

- Dorothy Owen, The medieval canon law : teaching, literature and transmission (Cambridge 1990) – with the focus on England.

- Walter Ullmann, Law and politics in the Middle Ages (London-Ithaca, NY, 1975) – a bit older, but still useful and free from any polemics.

- Jean Gaudemet, Le droit canonique (Paris 1988) – a very brief outline.

- Constant van de Wiel, History of canon law (Louvain 1991) – also brief, but touching contemporary canon law, too; an expanded version in Dutch: Geschiedenis van het kerkelijk recht (Leuven 2006), online, KU Leuven (PDF).

- Richard Helmholz, The spirit of classical canon law (Atlanta, GA, 1996) – excellent for further reading.

- Peter Erdö, Die Quellen des Kirchenrechts. Eine geschichtliche Einführung (Frankfurt am Main 2002).

- Kriston R. Rennie, Medieval canon law (Bradford 2018) – concise with a refreshing view on early developments.

- Mathias Schmoeckel, Kanonisches Recht : Geschichte und Inhalt des Corpus iuris canonici. Ein Studienbuch (Munich 2020).

For the study of medieval canon law one cannot miss the following books:

- Stephan Kuttner, Repertorium der Kanonistik (1140-1234). Prodromus Corporis Glossarum, part I (Città del Vaticano 1937; reprints 1973, 1981, 2013) – the classic repertory for manuscripts with texts concerning medieval canon law.

- Gabriel Le Bras, Charles Lefebvre and Jacqueline Rambaud, L’âge classique 1140-1378. Sources et théories du droit (Paris 1965; Histoire du droit et des institutions de l’Eglise en Occident, VII).

- Jean Gaudemet, Les sources du droit canonique, VIIIe-XXe siècles. Repères canoniques, sources occidentales (Paris 1993).

- Jean Gaudemet, Église et cité. Histoire du droit canonique (Paris 1998).

- Lotte Kéry, Canonical collections of the Early Middle Ages (ca. 400–1140) : a bibliographical guide to the manuscripts and literature (Washington, D.C., 1999) – “History of Medieval Canon Law”, Wilfried Hartmann and Kenneth Pennington (eds.).

- Detlev Jasper and Horst Fuhrmann, Papal letters in the early Middle Ages (Washington, D.C., 2001; History of Medieval Canon Law, 2) – for the early history of papal decretals.

- The history of medieval canon law in the classical period, 1140-1234. From Gratian to the decretals of pope Gregory IX, Kenneth Pennington and Wilfried Hartmann (eds.) (Washington, D.C., 2008; History of Canon Law) – at last an up to date very accessible introduction to medieval canon law during one of its most important periods

- Linda Fowler-Magerl, Ordo judiciorum vel ordo judiciarius. Begriff und Literaturgattung (Frankfurt am Main 1984).

- Ludger Körntgen, Studien zu den Quellen der frühmittelalterlichen Bußbücher (Sigmaringen 1993) – on the so called libri paenitentiales.

- Anders Winroth, The making of Gratian’s Decretum (Cambridge, etc., 2000).

- Melodie Eichbauer and Danica Summerlin (eds.), The Use of Canon Law in Ecclesiastical Administration, 1000–1234 (Leiden, etc., 2018).

- New discourses in medieval canon law research – Challenging the master narrative, Christoph Rolker (ed.) (Leiden-New York, 2019).

- Anders Winroth and John C. Wei (eds.), The Cambridge History of Medieval Canon Law (Cambridge, etc., 2022) – concise compared to the American project and uptodate.

- Christoph Rolker, Canon law in the age of reforms (c. 1000 to c. 1150) (Wahington, D.C., 2023)

The impact of medieval canon law on law in later centuries, in particular on judicial procedures, is the subject of essays in the series Der Einfluss der Kanonistik auf die europäische Rechtskultur, Orazio Condorelli et alii (edd.) (5 vol., Cologne-Weimar-Vienna 2009-2016), with each volume dedicated to a specific field of law.

Important are the following parts of the series Typologie des sources du moyen âge occidental, edited at Louvain-la-Neuve:

- Gérard Fransen, Les décrétales et les collections des décrétales (Turnhout 1972; Typologie, 2) – supplement, 1985.

- Gérard Fransen, Les collections canoniques (Turnhout 1973; Typologie, 10) – supplement, 1985.

- Odile Pontal, Les statuts synodaux (Turnhout 1975; Typologie, 11).

- Cyrille Vogel, Les “libri paenitentiales” (Turnhout 1978; Typologie, 27) – supplement by A.J. Frantzen, 1985.

- Peter Brommer, ‘Capitula episcoporum’. Die bischöfliche Kapitularien des 9. und 10. Jahrhunderts (Turnhout 1985; Typologie, 43).

- B.C. Bazàn, J.W. Wippel, G. Fransen and D. Jacquart, Les questions disputées et les questions quodlibetiques dans les facultés de Théologie, de Droit et de Médecine (Turnhout 1985; Typologie, 44-45).

- Linda Fowler-Magerl, Ordines iudiciarii and libelli de ordine iudiciorum (from the middle of the twelfth to the end of the fifteenth century) (Turnhout 1994; Typologie, 63).

Some scientific journals on medieval canon law:

- Zeitschrift der Savigny-Stiftung für Rechtsgeschichte, Kanonistische Abteilung – since 1910

- Bulletin of Medieval Canon Law (BMCL) – first in Traditio, independently since 1971, with a bibliography; issues from volume 30 (2013) onwards have been digitized at Legal History Sources

- Archiv für Katholisches Kirchenrecht

- Revue de Droit Canonique, Institut de droit canonique, Strasbourg – with also a useful links collection

- Revista Español de Derecho Canónico

- Rivista Internazionale de Diritto Comune – since 1990; with a bibliography of current publications

- Annuarium Historiae Conciliorum – one can search the bibliography online

- Concilium Medii Aevi – since 1998; all issues are online, with regularly articles touching on medieval canon law

The Pontificia Università Gregoriana has created an overview of relevant journals, including their availability online. Stéphane Boiron and Franck Roumy wrote for Forum Historiae Iuris in 2002 a fine overview of recent publications on canon law (in French).

The selective bibliography by Darío Ferreira-Ibarra, The canon law collection of the Library of Congress. A general bibliography with selective annotations (Washington, D.C., 1981; online, Hathi Trust Digital Library) gives some impression of the great variety of works and subjects in the field of canon law and its long history, and of the printed Early Modern literature, but the order of presentation of the 2,500 works mentioned is sometimes strange. Luckily the Library of Congress has developed a very differentiated classification scheme KBR for canon law.

Links

First, a number of online bibliographical databases:

- RI OPAC: Literaturdatenbank zum Mittelalter, Regesta Imperii, Akademie der Wissenschaften und Literatur, Mainz – a very useful free accessible online bibliography for medieval history; interface German and English

- GREGORIUS, Strasbourg – a bibliographical database on the history of canon law, maintained by François Jankowiak (Université Paris XI)

- KALDI: Kanonistische Literaturdokumentation Innsbruck – a bibliographical database for both medieval canon law and modern canon law

- Bibliografia Canonistica, Gruppo Italiano Docenti di Diritto Canonico – here, too, the main emphasis is on current canon law

- Datenbank, Institut für Kanonisches Recht, Universität Münster – a bibliographical project of all institutes for canon law in Germany, with some 40,000 titles; the emphasis is on modern ecclesiastical law

- Bibliografía canonica, Pontificia Università Gregoriana – mainly for modern canon law

- Index Canonicus: Intermationale Bibliographie für Kanonisches Recht und Kirchenrecht, IxTheo, Universität Tübingen – a bibliographical database with a search interface in six languages

- Bibliographia Synodalis Iuris Antiqui, Universität Bonn – an online bibliography of studies concerning church councils and synodes in Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages; alas the database isno longer available

- ORB Bibliographies – a basic bibliography on medieval canon law by Brendan McManus

Some online introductions:

- Netserf: Canon Law – a collection of links to texts of medieval canon law

- Kenneth Pennington, A Short History of Canon Law from Apostolic Times to 1917 – a splendid introduction on his portal site about medieval legal history

- Bio-bibliographies of medieval lawyers, Ames Foundation – for decades available at the website of Kenneth Pennington, Washington, D.C.; the new database mentions also anonymous works, and gives information on manuscripts, editions and literature

A selection of the main websites with online editions of the major textual sources:

- Gregory IX, “Liber Extra” – an online version at the Bibliotheca Augustana based on the edition of Emil Friedberg (1881), but without his annotation

- YperLiberExtra – thanks to the Università di Catania Friedberg’s edition of Gregory’s IX Liber Extra is available in a searchable form, with possibilities for saving and printing in PDF-format, or even adding one’s comments; the version at the Intratext Digital Library, too, has useful search functions

- The Editio Romana of the Corpus Iuris Canonici (1582) – a digital version created by the UCLA University Library of the official edition made by the Correctorses Roman ; there is also a sixteenth-century index on the decretals, called Margarita, and an index on the glossa ordinaria, called Materiae Singulares

- Decretum Gratiani – the edition of Emil Friedberg (1879), available online at the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Munich

- Domus Gratiani – homepage of Anders Winroth, Yale University

The texts of the Decretum Gratiani, the Liber Extra and the Liber Sextus of pope Boniface VIII at are also available at the website of the Scholastic Commentaries and Texts Archive (STCA). The online Repertorium Utriusque Iuris by Denis Muzerelle helps in identifiying individual elements such as canons and decretals in canonical collections and converting them to modern citation.

The Corpus Synodalium. Local Ecclesiastical Legislation in Medieval Europe (Rowan Dorin, Stanford University) offers both a repertory and online texts of many synodal statutes mainly between 1215 and 1400 with ample search possibilities. The project team created also a digital atlas of medieval dioceses and ecclesiastical provinces (1200-1500) and a bibliography.

A number of institutions and projects:

- Stephan Kuttner Institute of Medieval Canon Law – an international research institute, founded in 1955, in Munich since 1996; in 2013 the library moved to Yale University; news and announcements appear regularly at Facebook.

- Iuris Canonici Medii Aevi Consociatio (ICMAC) – the International Society for Medieval Canon Law has a website at the University of Kentucky, with among the resources its own news bulletin, Novellae – there is a Novellae newsgroup at Facebook.

- Church, Law and Society in the Middle Ages (CLASMA) – an international network of scholars doing research in the field of medieval canon law.

- The Virtual Medieval Canon Law Library, Colby College and Columbia University – a most useful selection of digitized works

- SCTA Reading Room, Scholastic Commentaries and Texts Archive – an initiative to create a general online text archive for medieval learned texts, including some major texts for canon law and some canon law statutes

- Penance, Penitential Tradition, and Pastoral Care in the Middle Ages, Roy Flechner (University College, Dublin) and Rob Meens (Universiteit Utrecht) – originally a blog, but with good sections on literature and relevant websites.

- Anglo-Saxon Canon Law, Michael D. Elliott (Toronto) – a project with not only (preliminary) editions of several texts, but also an excellent thematic links collection, nearly a portal to medieval canon law.

- The Anglo-Saxon Penitentials, Allen J. Frantzen – penitentials in Old English.

- RELMIN: The legal status of religious minorities in the Euro-Mediterranean world (5th-15th centuries), John Tolan, Université de Nantes and Maison des Sciences de l’Homme, Nantes – one of the results of this project is a database with relevant juridical texts which will be expanded.

- Centre Droit et Sociétés Religieuses, Université Paris XI, Faculté Jean Monnet – a number of works in the library has been digitized in Yvette, the digital library of the Université Paris-Sud

- Fulmen. Censures canoniques et gouvernement, IVe-XXIe siècles – a blog of a French research project about the history of excommunication, interdict and other punishments

- Promptuarium Ecclesiasticum Medii Aevi, Bernd-Ulrich Hergemöller, Universität Hamburg – a useful Latin-German dicitonary for ecclesiastical terms

A number of websites helps you to use textual sources and archival records online:

- Europeana Regia – within this project of a number of major libraries to reconstruct and create in digital from three libraries you could find also medieval legal manuscripts, in particular from the Carolingian period; here a preliminary overview (December 2011) – after the closure of this project a new IIIF compliant version was launched at Biblissima.

- Taxatio Ecclesiastica Angliae et Walliae Auctoritate P. Nicholai IV, University of Sheffield – the searchable version of the edition from 1802 by the Record Commission concerns an unique assessment of ecclesiastical wealth in England and Wales from the years 1291-1292.

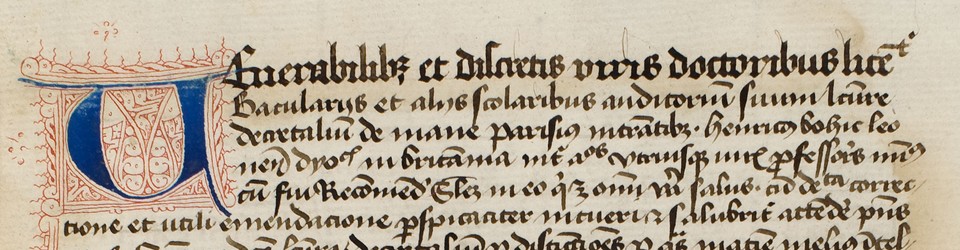

- Henri Bohic, un juriste breton au Moyen Âge, Jean-Luc Deuffic – a site about a fourteenth-century French canonist; alas the site has been discontinued; partially archived version, 2012, Internet Archive

- Biblioteca: Manuali e Letteratura, Istituto Centrale per gli Archivi, Rome – digitized older literature concerning archives, diplomatics and palaeography, with for example the Relatio romanae curiae forensis by G.B. de Luca, the Bullarium Romanum, Franz Steffens’ Paléographie latine (Paris 1910), and also Costamagna’s more recent introduction to paleography (1987).

- Schrifttafeln, Historische Hilfswissenschaften and Fragmentarium, Universität Freiburg, Schweiz – digitized versions of both Franz Steffens’ original Lateinische Paläographie (Trier 1909) and the French translation, Paléographie latine (Paris 1910).

A number of online resources shows the importance of the pope and papal courts:

- Repertoria Romana, Deutsches Historisches Institut, Rome – searching in the databases of the Repertorium Germanicum and the Repertorium Poenitentiariae Germanicum.

- Repertorium Officiorum Romane Curie (RORC), Thomas Frenz – a database for finding officials of the papal curia in the fifteenth and sixteenth century; interface Latin.

- Materialen zur apostolischen Kanzlei, Thomas Frenz – a supplement to his book from 2000 and references to images of papal charters.

- Bibliographie zur Diplomatik, Thomas Frenz – this introduction to medieval diplomatics is particularly strong for papal charters.

- Papal Documents, Archivio Segreto Vaticano – Internet Archive – an archived version (2010) of a most useful basic introduction, available in six languages.

- Regesta Pontificum Romanorum Online, Papsturkunden des Mittelalters und der Frühen Neuzeit, Göttingen – a tool for researching papal charters isued until 1198; access after registration – a new edition of “Jaffé” is being published [Regesta Pontificum Romanorum, I (ab a. 39 – ad a. 604), Klaus Herbers et alii (eds.) (Göttingen 2016); II (ab a. 604 – ad. a. 844 (2017); III (ab a. 844 – ad a. 1024) (2017); IV ((ab a. 1024 ad a. 1073) (2020)] – you can consult online at the MGH website the two volumes of the second edition, “Jaffé-Ewald” (I, 1885 and II, 1888)

- August Potthast, Regesta pontificum romanorum inde ab a. post Christum natum MCXCVIII ad a. MCCCIV (2 vol., Berlin 1874-1875) – the sequel to Jaffé for the period 1198-1304; online, Hathi Trust Digital Library – you can search for destinataries of these papal bulls at Adressaten/Empfänger in Potthast: Regesta Pontificum Romanorum, Charters Encoding Initiative, Munich

- Database of the letters of pope Gregory VII (1073-1085), Christian Schwaderer, Tübingen – a research tool for the textual transmission of these letters.

- Die Register Innocenz’ III., 13. Pontifikatsjahr, 1210/1211: Texte und Indices, Andrea Sommerlechner and Hedwig Weigl (eds.) (Vienna 2015) – a digitized volume in the ongoing series edited by Austrian scholars; the following volume, Die Register Innocenz’ III. 14. Jahrgang (1211/1212). Texte und Indices, Andrea Sommerlechner e.a. (eds.) (Vienna 2018) is available online, too, as is Band 9, Die Register Innocenz´ III., 9. Band, 9. Pontifikationsjahr, 1206/1207. Texte und Indices, A. Sommerlechner e.a. (eds.) (Vienna 2004), and now also Band 15 for 1212-1213, A. Sommerlechner e.a. (eds.) (Vienna 2022) and Band 3 for 1201-1202, W. Maleczek (ed.) (Vienna 2023)

- Die Briefe Papst Clemens’ IV. (1265–1268), Matthias Thumser, Humboldt Universität Berlin and MGH – a preliminary online edition of 556 letters, now published as Epistole et dictamina Clementis pape quarti. Das Spezialregister Papst Clemens’ IV. (1265–1268) (Wiesbaden 2022; MGH, Briefe des späteren Mirttelalters, 4)

- Buttlari de Catalunya: documents pontificis originals conservats als arxius de Catalunya (1198-1417), Roser Sabanés i Fernandez and Tilmann Schmidt (eds.) (3 vol., Barcelona 2016) – an example of a modern edition of papal documents for one region; online, vol. I, II and III (PDF)

- DelegatOnline (FLEP-HUN) – a project for a prosopographical database concerning (papal) legates and their activities in Hungary (eleventh-thirteenth centuries); interface Hungarian and English.

- Étienne Baluze, Vitae paparum avenionensium, Guillaume Mollat (ed.) (4 vol., Paris 1914-1928) – a digital version created by the Centre Pontifical d’Avignon (Université d’Avignon) of Mollat’s modern edition of Baluze’s book about the popes in Avignon from 1693.

- APOSCRIPTA -Lettres des papes, Telma, IRHT with the Fulmen project- a project for a database with medieval papal letters, including decretals; currently with some 26,000 entries, mainly for the twelfth and thriteenth centuries; interface French; note the extensive list of editions

- Gallia Pontificia – Papsturkunden in Frankreich, Deutsches Historisches Institut, Paris – a database version of this long-running project, in beta phase; similar projects exist for other countries

Some classic editions of papal charters and letters – the Registres et lettres des Papes du XIIIe siècle (32 volumes, Rome 1883-) and the Registres et lettres des Papes du XIVe siècle (48 volumes, Rome 1899-) – can also be searched online at the subscribers-only database Ut per litteras apostolicas (Brepols). The Archivio Segreto Vaticano has created cd-roms for four major series of papal registers. Good introductions to palaeography and diplomatics with a full repertory of relevant links are for example present at the French portal Ménestrel. In print you will benefit from Thomas Frenz, Papsturkunden des Mittelalters und der Neuzeit (2nd ed., Wiesbaden 2000).

The Vatican Film Library at Saint Louis University, St. Louis, MO, offers not only microfilms but also a useful overview by genre of manuscripts at the Vatican Library, an overview of papal registers, and the Metascripta portal for online research with Vatican manuscripts. On the page for medieval law I mention more (digitized) microfilm collections. Microfilms with canon law texts can be found for example in Berkeley, Frankfurt am Main, Munich, Milan and Würzburg (PDF).

The papacy is the object of many studies. Legal matters are not forgotten in A companion to the medieval papacy. Growth of an ideology and institution, Keith Sisson and Atria Larson (eds.) (Leiden-Boston, 2016).

Some sites are concerned with manuscripts on canon law:

- Initia operum iuris canonici medii aevi – Giovanna Murano, Florence, has created this register of incipits (beginnings) for texts concerning medieval canon law; see also the overview of medieval juristic manuscripts of Brendan McManus, Bemidji State University.

- Carolingian Canon Law Project, University of Kentucky – a project with manuscripts directed by Abigail Firey.

- Leipziger Datenbank zu den mittelalterlichen juristischen Handschriften – these pages aim at creating an uptodate version of the Verzeichniss der Handschriften zum römischen Recht bis 1600 (4 vol., Frankfurt am Main 1971) by Gero Dolezalek and Hans van de Wouw; in July 2012 the database Manuscripta Juridica was launched at Frankfurt am Main. It will eventually include also canon law manuscripts.

- Manuscripts of the Liber Extra – a preliminary list of signatures by Martin Bertram, updated in 2010 and 2014.

- Progetto Mosaico, Università degli Studi di Bologna – a project for a digital library of medieval legal manuscripts, with the Apparatus decretalium by Goffredo da Trani (ms. Montecassino 266), and information on manuscripts containing the Authenticum and arbores actionum.

- Giovanni d’Andrea Manuscripts – Mapping law in medieval Spain, The Malta Study Center and Virtual Hill Museum and Library, Saint John’s University – a digital presentation about manuscripts in Spain with the works of Johannes Andreae (ca. 1270-1348)

Early Modern and current canon law

The main focus of this page is on medieval canon law, but it is useful to add at least some resources concerning later sources:

- The Council of Trent (1545-1563): Canones et Decreta (Latin, Documenta Catholica) – English: The Council of Trent, transl. J. Waterworth,1848 (Hanover Historical Texts), see also the searchable version at Intratext – Spanish translation at Intratext – a sixteenth-century edition, Canones et decreta Sacrosancti oecumenici et generalis Concilii Tridentini (…) (Compluti 1564) has been digitized in an easy searchable version in the Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes – critical edition by the Görres-Gesellschaft: Concilium Tridentinum. Diariorum, actorum, epistularum, tractatuum nova collectio (19 vol., Freiburg 1901-2001)

- Codex Iuris Canonici 1917: Latin, Italian, French and Czech (Pontificia Università Gregoriana) – there is a searchable version of the Latin text at Intratext.

- Codex Iuris Canonici 1917: Fontes, Pontificia Università Gregoriana – the tables of Pietro Gasparri form a concordance between the Corpus Iuris Canonici and the Codex of 1917, see also the digitized volumes (9 vol., Rome 1923-1939), Internet Archive

- Documents of the Second Vatican Council (1962-1965), Vatican – the Latin versions and several translations of the constitutions, decrees and declarations – at Intratext you can find searchable translations in various languages, in some cases not for every document

- Codex Iuris Canonici (1983): the Pontificia Università Gregoriana offers a multilingual version and numerous separate translations – a searchable Latin version can be found at Intratext – there is an online English translation by the Canon Law Society of America, and another one at Intratext, where you can find also translations into German, French, Spanish and other languages

- Codex canonum ecclesiarum orientalium (CCEO, 1990) – Intratext

- CCEO, Pontificia Università Gregoriana – the Latin text and several translations

The Ponticia Università Gregoriana presents a useful overview of digitized historical sources of canon law.